Chelsea // Native News

Browning, Montana //

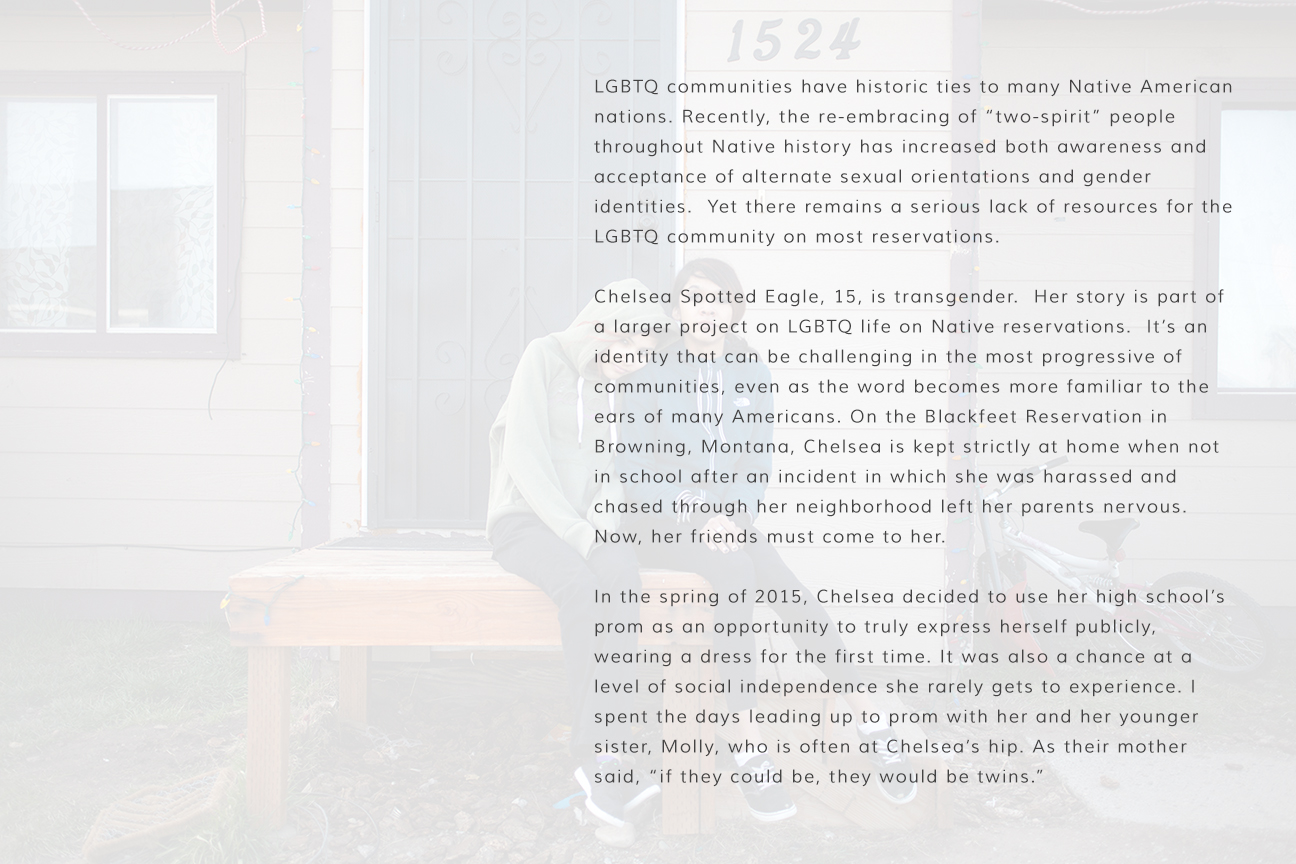

When 15-year-old Chelsea Spotted Eagle committed herself to attending prom at Browning High School on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Browning, Montana, it was a decision she did not take lightly. It was the first time she would wear a dress in public.

Chelsea is transgender. After an incident in which she was harassed and chased through her neighborhood, her parents were left nervous and zealously protective. She is kept strictly at home when not in school, and her friends have gotten use to coming to her if they wish to hang out. Her first prom represented not only a chance at public self-expression, but also an opportunity for social independence she rarely gets to experience.

Her story is part of a larger project on LGBTQ life on Native American reservations. To identity as transgender can be challenging in the most progressive of communities, even as the word becomes more familiar to the ears of many Americans. On the Blackfeet Reservation, as in many rural communities, there remains a serious lack of resources for the LGBTQ community.

“I want him to get out there in the world, to be free. And not to feel like he’s trapped,” said her mother, Lydia Spotted Eagle, who still sometimes uses the pronouns of the son she gave birth to. “Not just because he’s transgender, but because he’s a Native American on a reservation. And around here we know there’s not a whole lot for our kids.”

Browning, Montana //

When 15-year-old Chelsea Spotted Eagle committed to attending prom at Browning High School on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in western Montana, it was a not decision she took lightly. It would be the first time she would wear a dress in public.

Chelsea - who has since changed her name to Deaven - is transgender. After an incident in which she was harassed and chased through her neighborhood, her parents were left nervous and protective. She is kept strictly at home when not in school, and her friends have gotten use to coming to her if they wish to hang out. Her first prom represented not only a chance at public self-expression, but also an opportunity for social independence she rarely gets to experience.

Her story is part of a larger project on LGBTQ life on Native American reservations. To identity as transgender can be challenging in the most progressive of communities, even as the word becomes more familiar to the ears of many Americans. On the Blackfeet Reservation, as in many rural communities, there remains a serious lack of resources for the LGBTQ community.

“I want him to get out there in the world, to be free. And not to feel like he’s trapped,” said her mother, Lydia Spotted Eagle, who still sometimes uses the pronouns of the son she gave birth to. “Not just because he’s transgender, but because he’s a Native American on a reservation. And around here we know there’s not a whole lot for our kids.”

Photographed for Native News

Browning, Montana //

When 15-year-old Chelsea Spotted Eagle committed herself to attending prom at Browning High School on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Browning, Montana, it was a decision she did not take lightly. It was the first time she would wear a dress in public.

Chelsea is transgender. After an incident in which she was harassed and chased through her neighborhood, her parents were left nervous and zealously protective. She is kept strictly at home when not in school, and her friends have gotten use to coming to her if they wish to hang out. Her first prom represented not only a chance at public self-expression, but also an opportunity for social independence she rarely gets to experience.

Her story is part of a larger project on LGBTQ life on Native American reservations. To identity as transgender can be challenging in the most progressive of communities, even as the word becomes more familiar to the ears of many Americans. On the Blackfeet Reservation, as in many rural communities, there remains a serious lack of resources for the LGBTQ community.

“I want him to get out there in the world, to be free. And not to feel like he’s trapped,” said her mother, Lydia Spotted Eagle, who still sometimes uses the pronouns of the son she gave birth to. “Not just because he’s transgender, but because he’s a Native American on a reservation. And around here we know there’s not a whole lot for our kids.”

photographed for Native News